Blogs

Press Freedom is an important component of the right to Freedom of Expression and the respect for fundamental freedoms, that are enunciated in pretty much all international legal instruments of intent. The vast majority of states in the world committed to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 16.10 which calls upon States to “ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements”. On the African continent, members states of the African Union (AU) equally affirmed Aspiration 3 of the Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want, which envisions “an Africa of good governance, democracy, respect for human rights, justice and the rule of law”. Also under the aegis of the AU, in May 2022, the media stakeholders attending the African Media Convention in Arusha expressed an urgent need for improved synergies between the media on the continent, governments, internet intermediaries, private and public sectors, civil society, national as well as regional human rights organizations and researchers to mitigate the effects of the digital onslaught on journalism and the media.

Sadly, despite their ratification of several international treaties committing to Press Freedom, the state of media freedoms are very dire at present and have actually been deteriorating with great speed recently. According to the preliminary findings on Round 11 of AFIDEP’s Africa Integrity Indicators (AII), only two countries (Namibia and South Africa) scored good results (scores of 75) while four countries (Senegal, Tunisia, Cote d’Ivoire and Togo) performed moderately (Scores of 50) on indicator 55 which assesses pre-publication censorship of the media by the state and government’s promotion of the media’s self-censorship. The highest possible score is 100. What this means is that the vast majority of the countries (48) posted adverse scores on this indicator showing very clearly how prevalent media censorship is in Africa. In the worst-case scenarios, in countries like Eritrea, there is absolutely no private media, whereas in other cases the prevalent trends are public media that are brazenly biased towards governing parties in their coverage while journalists are hounded, brutalized and jailed for coverage that is critical of government. These preliminary findings correspond with concerns issued by media stakeholders at the 2022 World Press Freedom Media Convention in Arusha, Tanzania which stated that, across the continent, several journalists and online content creators were arrested, detained and some prosecuted for their online initiatives and content. The media stakeholders present also stated in their resultant Arusha Declaration that the authorities in different African countries have largely relied on the retrogressive provisions within the enacted cyber laws and or penal codes.

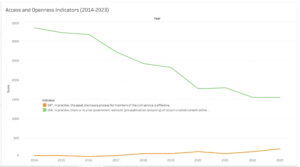

In recent times, there is a lot on new media online whereas conventional media has also significantly transcended to the online space and thus it is important to also assess the online media and citizen content space. On indicator 55 which assesses pre-publication censorship of online news outlets and citizen created content as well as well as government promotion of the self-censorship of online content and social media, only four countries (Namibia, South Africa, Mozambique and The Gambia) posted good performances. 10 countries performed moderately including Ghana, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, The Congo (Brazzaville), the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Angola, Kenya and Malawi. The rest of the countries (40) posted poor scores. In the worst of the cases such as Ethiopia and other countries experiencing armed conflict, the state periodically shut down the internet and curtailed access to social media. In countries like Uganda, editors of online media outlets and prominent bloggers were arrested because of content that was critical of the government. This current situation represents a marked decline from 2014 and shows how state censorship of the media has actually worsened to date.

Figure 1: Cumulative Country Performances on Access and Openness Indicators Since 2014

The various international legal instruments of intent that most African countries are signatory to state that press freedom is a necessary element to a safe, inclusive and conducive environment for electoral participation. The AII also has Indicator 23 which assesses political parties’ and public office candidates’ equitable access to the public media. According to the preliminary findings of Round 11, only five countries (South Africa, Namibia, Senegal, Morocco and Burkina Faso) had good scores. The inclusion on Burkina Faso in the top performers is very interesting given that it very recently experienced a coup. 9 countries performed moderately including Rwanda, Lesotho, Kenya, Algeria, Niger, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Guinea Bissau and The Gambia while the rest of the countries (40) performed poorly. This state of affairs further validates the already stated finding that most of public media is biased towards the campaigns of incumbent political parties and candidates.

In recent times, there has also been growing criminalisation of free speech online mostly using legislation that purportedly aims to combat “fake news” and “false news”. Regulatory requirements for digital media outlets and citizen content creators to be licenced by states and to pay fees and levies, coupled with the intimidation, jailing and brutalization of media workers and online content creators are some of the pressing challenges facing the media today. Some countries have barely relaxed the emergency legislation that they used during the height of Covid 19 lockdowns and are still actively using the laws to curtail media freedoms.

The AII also has other indicators that have a bearing on the state of Press Freedom, such as Indicators 45 and 47 which assess issues of asset disclosures of public officials and Indicators 49 and 51 which focus on political finance accountability, particularly assessing whether or not political parties publicly disclose their sources of funding. These were the indicators that had the worst scores in the recently released preliminary findings and this is an indictment on press freedom as it obviously indicates that even the media could not access this crucial information from states and political parties that are in the public interest and are important for public accountability.

The woeful performance of the continent generally on indicators related to press freedom make it very clear that there is need for countries introspect deeply on how their media repression is impacting on the enjoyment of citizen rights to Freedom of Expression to which they voluntarily committed themselves in various international treaties. Countries need to relax punitive legislation and unwarranted regulatory mechanisms that stifle the free flow of information which is a crucial ingredient of democracy. States also need to submit themselves to higher standards of ensuring the safety of media workers and providing a functional environment for their operations.

Mziwandile Ndlovu is a Research and Policy Analyst working with the African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP). He currently works on the Africa Integrity Indicators (AII) project as Anglophone Africa Project Manager.