Blogs

At AFIDEP, we have been engaging Members of Parliament (MPs) in Africa to improve their understanding of the demographic dividend paradigm. This is important because many African countries are increasingly embracing the demographic dividend paradigm as their development framework in order to spur transformative socio-economic development. MPs therefore need a good understanding of the demographic dividend paradigm if they are to effectively deliver their oversight, legislative, and representative functions.

The demographic dividend refers to the accelerated economic growth that is initiated by a rapid decline in fertility and mortality that results in a change in the age structure from one dominated by child dependents to one dominated by economically productive working adults.

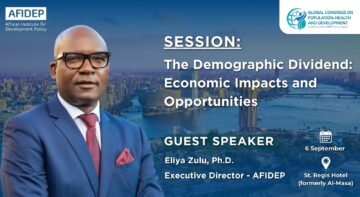

We have been engaging MPs through regional networks such as the Network of African Parliamentary Committees on Health (NEAPACOH) and through national parliaments, mainly in Kenya and Malawi. During these engagements, MPs have been asking particular questions, and in this blog, we provide responses to these questions based on conversations with Nyovani Madise (PhD, a Professor of Demography and Social Statistics at the University of Southampton in the UK, Eliya Zulu (PhD, a demographer and Executive Director of AFIDEP), and Bernard Onyango (PhD, a demographer and Knowledge Translation Scientist at AFIDEP).

Question 1: You are asking African countries to reduce the number of children that families are having, but we know that a country like China, which reduced its fertility to one child per family, is now facing the challenge of an aging population with no workers (labour). Why do you want African countries to face the same problem of an aging population?

Response

China is facing a severe problem with a fast aging population because it adopted a harsh policy of one-child per family to address a real problem of high population growth rates in the 1960s and 1970s. However, the policy was implemented in a coercive manner and over a prolonged period of time. Now, African countries can avoid this problem of fast aging populations by encouraging families (not coercing) to reduce births to two children, which is called replacement fertility, as it replaces the father and the mother. This will stabilise population growth and reduce the severity of the problem of aging populations. If birth rates in Africa fall to below replacement levels, and there are already signs of this in some of the smaller island countries, then over time, the populations will age.

Also, if African countries make the right investment to harness the demographic dividend, then the incomes of people will rise, and all things being equal, most people will be able to save enough money for retirement. Thus, the aged population, when it happens, will be less burdensome to the working age population. Fertility in Africa needs to fall sharply if the continent is to harness the demographic dividend. Implementing actions that enable countries to reap a sizeable demographic dividend will help African countries to experience economic growth and be better prepared for aged populations.

Finally, it is in the interest of African countries to manage their fertility, which in many cases is declining too slowly and therefore the population growth rate remains very high. Take the practical example of Tanzania where, on average, women currently expect to have five children over their lifetime. Going by the trends in decline in fertility, in just 15 years between 2015 and 2030, it is projected that Tanzania’s population will rise from 53 million to 83 million people, and by 2050, unless birth rates slow substantially, the population will rise to 137 million people. This kind of rapid population growth has serious implications for both governments and households starting with the provision of essential needs and services.

Question 2: From the evidence, countries are making strides in reducing fertility. But what should be the right number of children that every woman or family should have?

Response

This is a tricky question because it will not be right for African countries to coerce their citizens to have a certain number of children. Even then, African countries, especially in the West, Central, Eastern, and some parts of Southern Africa, still have very high fertility rates (ranging between 4.0 to 8.0 births per woman), and if these persist, these countries will continue to struggle to realise meaningful socio-economic development. What these countries need to do is to encourage citizens to have fewer children and provide the interventions or services that enable citizens to have fewer children. To stabilise the growth of their populations, these countries should encourage families to have two children, which is the replacement fertility level (where families replace the father and the mother). Countries’ efforts to reduce fertility rates must be voluntary and not coercive.

Question 3: What should we tell our constituents, the people who vote for us, to do in order to bring down the high fertility rates?

Response

As MPs, you have a leadership role in the country and in the eyes of the people who voted for you. Therefore, through this role, you can advocate for smaller families within your constituencies, encouraging families to have the number of children that they are able to care for in terms of providing basic needs (food, education, healthcare, clothing, etc.). You can also advocate for your constituents to keep girls in school. This is an important intervention that enables girls to delay the start of child bearing. But also, evidence shows that girls with higher levels of education (college or university) tend to have fewer children than their illiterate or semi-illiterate counterparts. Good education gets girls into meaningful employment, which contributes to socio-economic growth. It also gives girls confidence in decision-making for better health for themselves and their families. Advocating and championing for smaller families and keeping girls in schools are some immediate interventions that MPs can implement in their communities. Also, men should be encouraged to be involved in family planning since our societies have in the past treated men as passive on-lookers in family planning programmes despite their immense role in decision-making in the family.

Question 4: What is so new about the demographic dividend framework since African countries have already been investing in the sectors highlighted by the framework?

Response

Yes, African countries have been investing in the priority sectors outlined by the demographic dividend paradigm. However, we know that these countries are making very slow progress and that is why they have failed to achieve their development goals over the years. The demographic dividend paradigm provides a mindset shift on how countries should be prioritising their development efforts in order to realise transformative socio-economic development. The framework provides countries with various development scenarios based on the reforms they make and the resources that they invest. Countries need to invest in family planning to reduce the high population growth rates, provide good quality education for both boys and girls, invest in health, create an enabling environment for creation of decent jobs and economic reforms that encourage investment, prevent further degradation of our environment, and promote good governance and accountability in both the public and private sectors. The demographic dividend paradigm is helping make the investment case for people-centered development. It is also providing a life-course approach to investing in human capital focusing on the need for early investments in young people if we expect to get optimal productivity from them later in life.

Related Posts