Blogs

Today, Africa has the world’s highest fertility rates. On average, women in Sub-Saharan Africa have about five children over their reproductive lifetime, compared to a global average of 2.5 children. Research shows that the “demographic transition,” the name for the change from high death and fertility rates to lower death and eventually lower fertility rates, has proceeded differently here from other regions in the developing world.

Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa experienced slightly higher pre-transitional levels of fertility, have had a much later onset of transition, and have transitioned at a much slower pace. Fertility rates in the region declined by 37 percent between 1960 and 2005, much less than the 61 percent decline in Asia and Latin America over the same period.

Fertility rates matter beyond population growth: persistently high fertility rates have been associated with poor economic development, low living standards, low educational attainment, and high disease burden”all areas in which Sub-Saharan African countries generally lag behind the rest of the world.

However, it’s important to take note of the high heterogeneity of fertility rates on the sub-continent, which is masked by lumping all African countries together.

Although most countries have four or more children per woman, a few are below or near replacement fertility levels, including Mauritius (1.5), Seychelles (2.3), South Africa (2.4), and Cape Verde (2.4). And countries such as Rwanda have recorded marked fertility decline in recent years. The fertility rate in Rwanda declined by about two children between 2005 and 2014. Further, fertility decline has resumed in most countries that had experienced a stall, for example in Kenya.

Indeed, three factors are expected to drive fertility decline in Sub-Saharan Africa in the near future.

New Optimism

First, the new wave of optimism sweeping across the region about the potential of the demographic dividend for improving economic outcomes has created an advocacy platform for fertility decline.

The “demographic dividend” is the rapid economic growth that can be realized when a country has a large proportion of working-age adults relative to the dependent population (children below 15 and elderly people older than 65). If from current high levels, the resulting “youth bulge” will yield large populations with great potential to contribute to economic growth through their productivity, consumption, and savings.

African leaders have in the past opposed use of contraceptives, viewing them as a Western imposition to reduce African populations. But the promise of the demographic dividend has ignited a resurgence of interest in population and family planning issues. Many leaders realize the role fertility decline plays in harnessing the demographic dividend and are thus advocating for improved family planning programs.

For example, President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda applauded the linkages between population and development that showed how countries could take advantage of their population dynamics to accelerate socioeconomic transformation during the 2014 inaugural Family Planning Conference in Uganda.

“Family planning is good for the health of the child and the mother, for the wellbeing of the family, and the whole country,” he said. “It’s about holistic development that starts with the realization that having too many children is not good for development.”

Malawian President Arthur Mutharika, in a 2015 United Nations Population Fund-led delegation meeting to discuss how Malawi can harness the demographic dividend to accelerate socioeconomic transformation, noted that the country is sitting on a time bomb as far as high population growth is concerned, and promised to strengthen the country’s family planning program.

New Funding

Secondly, access to reproductive health services, particularly family planning services, has become a global development priority, ending a decade of neglect when global attention and funding was directed towards HIV/AIDS programs.

A case in point is the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning, which generated $2.6 billion in financial commitments from global donors to support family planning. The summit set an ambitious goal to provide access to modern contraceptive methods to an additional 120 million women and girls in the world’s 69 poorest countries by 2020.

As a result, in 2014, donor government contributions towards bilateral family planning programs in low and middle-income countries increased by 9 percent over 2013 levels and by 32 percent over 2012 levels. In 2015, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation further increased its funding to family planning programs by 25 percent, which translates to an additional $120 million dollars spread over three years.

New Demand

Last but not least, there is increasing demand for family planning services, including in countries which have historically recorded very low levels of contraceptive use. About 58 percent of women in Sub-Saharan Africa are not using modern methods of contraception, though many would like to.

Demand and use vary: Countries in East and Southern Africa record high demand for modern contraceptives, and more than half (54 percent) has been satisfied. By contrast, only about one fifth (22 percent) of the total demand for contraceptives in countries in has been satisfied. Less than 10 percent of married women use modern contraceptives, and about one in every three women in Central and West African countries want to limit or delay childbearing but are not using any method of contraception.

This pent-up demand can serve as an estimate of what the prevalence of modern methods of contraception might be if the existing need was met. Meeting all unmet demand would have major implications for fertility decline in Africa. The end result of a successful campaign would be a reduction of unintended pregnancies and births, and eventually a reduction of fertility rates.

“

Taking advantage of these factors will require concerted efforts from governments, donors, the private sector, and communities, including political will, targeted resource allocation, and implementation of effective programs. If this is done, then the fertility decline in Africa will come of age, and the narrative will change from “not possible” to “it’s happening!”

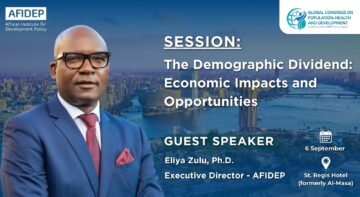

Eunice Mueni is a knowledge translation officer at the African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP), and currently also a Southern Voices Network scholar at the Wilson Center from April to June 2016.

Related Posts