Blogs

In recent years, the demographic dividend has garnered enormous traction in African policy circles, and leaders and policymakers have begun to see it as a strategy for achieving their economic growth targets.

Africa has the youngest population in the world. About 43 percent of the population of sub-Saharan Africa is younger than 15, while about two in every three people are below 25. In absolute numbers, young people between 10 and 24 years numbered 309 million in 2015, and are expected to increase to a massive 447 million by 2030. Taking advantage of this key resource can change the economic landscape of not only the region, but the globe.

Africa will account for nearly all of the growth in the global labor force by 2100, and the share of the global labor force that is African will increase from about 10 percent to 37 percent. Is Africa ready to take over the global labor market? How do African leaders get the economic and social policy mix right to ensure that this potential is not wasted?

The Employment Problem

African governments will face a formidable challenge in taking advantage of the boom in young adults. Currently, young people are four times more likely to be unemployed than adults. Youth unemployment varies across Africa ranges from 8 percent in Nigeria to 51 percent in South Africa.

Among those who are employed, most are engaged in vulnerable employment, like subsistence agriculture and informal self-employment in the services sector, which leaves them poor and unable to fully contribute to economic growth.

An International Labour Organization survey on transition to the labor market showed that although more than half of youth work, the quality of their employment is often poor, making it difficult for them to make the most of their economic potential. The Brookings Institution’s Foresight Africa report shows that only 28 percent of workers have stable, wage-paying jobs.

Youth unemployment and underemployment undercuts productivity, spending, and investment, stunting national growth. Informal and precarious working conditions mean many young people lack social protection and are forced into poverty.

“Young people are four times more likely to be unemployed than adults”

Practical Education Required

The ability of African governments to capitalize on the potential of youth is also affected by a severe mismatch between what employers say they need from workers and what young people can offer.

A report by the Brookings Institution this year found a “100-year gap“ between educational outcomes in developed and developing countries. Missing for many African countries is the teaching of critical thinking, teamwork and cooperation, communication, self-control, perseverance, and collaborative problem solving, which are increasingly in demand by the labor market. These “21st-century skills“ are correlated with higher academic achievement in school, higher wages, and lower levels of crime.

The skills mismatch is the result of poor quality education and a failure to link education curriculums with the needs of the market. Although net enrollment rates in primary education have improved tremendously in most African countries thanks to the Education for All movement and Millennium Development Goals, the needle has not moved much in access to secondary and tertiary schools or vocational training. Four in every five children of primary school age were in school in 2012, but in lower and upper secondary schools, gross enrollment rates were just 50 percent and 32 percent, respectively. In total, 121 million young people “ 12 percent of the population “ were not in school in 2012.

What’s a Policymaker to Do?

None of these challenges are insurmountable. Improving human capital, providing high quality jobs, and addressing infrastructure gaps top the list of policy changes required to tap into Africa’s huge labor force. Investment in education and training is essential in building an educated and skilled workforce and to encourage innovation.

The Sustainable Development Goals encourage these objectives. Goal four calls for universal education, from pre-primary through secondary, with relevant and effective learning outcomes, while goal eight calls for providing high quality jobs that pay good wages. Leveraging the attention provided by the SDGs could give African leaders the support needed to make these changes. As demographer Wolfgang Lutz has said, “human capital is the ultimate resource for sustainable development.”

But careful thinking and strategizing is required because of the magnitude of the investments needed. Solutions must go beyond improving access to education, also focusing on quality.

“Human capital is the ultimate resource for sustainable development”

Evidence shows that differences in learning outcomes “ not schooling levels “ explain variations in economic growth across countries. In fact, the high-level learning achieved in East Asia during its demographic bonus years helps explain the difference in economic growth from 1960 to 2000 compared to Latin America, which had similar levels of school completion but lower levels of learning.

To address un- and under-employment rates, job creation efforts will be needed at an unprecedented rate: about 18 million a year across the continent between 2010 and 2035. Increasing manufacturing and global trade will be key in this endeavor. Focusing on low-skilled industries can provide jobs to the poorly skilled out-of-school population in addition to providing more resources to invest in the education system to prepare youth for higher-skilled positions.

A recent Overseas Development Institute report identifies a number of promising manufacturing sub-sectors including garments and textiles, agro-processing and horticulture, automobiles, and consumer goods. As the rest of the world ages, Africa can seize the opportunity and integrate its labor force into growing global value chains. Opening up trade will attract capital and technology transfers, and there’s an opportunity for the continent to take up higher value-added, export-led manufacturing.

Governments and the private sector must also invest in workforce development and training programs that recognize that most youth will be self-employed or work for small enterprises. Entrepreneurship training and mentorship should rank high in these programs.

Timing is of the essence, as these policy changes and investments must be done before the majority of today’s youth reach working age.

This article also appeared on the Africa Program’s “Africa Up Close’ blog.

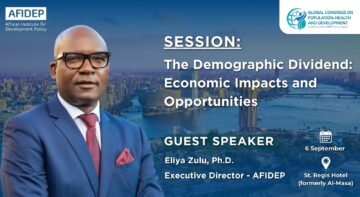

Eunice Mueni is a Southern Voices Network scholar at the Wilson Center from April to June 2016. She is a knowledge translation officer at the African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP), a member of the Southern Voices Network.

Related Posts