Blogs

Over the past 30 years, there have been tremendous efforts toward improving the outcomes of patients suffering from tuberculosis (TB). However, TB continues to be a high burden globally. In 2019 alone, there were at least 10 million TB infections and 1.4 million deaths worldwide. Due to improvements in treatment over the last 20 years, it is approximated that over 80% of patients suffering from pulmonary TB survive treatment (treatment completion or cure), although it is also estimated that a quarter of these survivors develop post-TB impairments.

To this end, the African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP) implemented a one-year project on Post-TB Lung Disease in partnership with the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM), the National Tuberculosis, Leprosy and Lung Disease Programme (NTLP), Kenya and the National Tuberculosis-control Programme (NTP), Malawi. The project aimed at engaging stakeholders in Kenya and Malawi to identify potential models of post-TB care, barriers to implementation and existing data gaps on post-TB disease. In-depth interviews were conducted with various stakeholders including healthcare providers, policymakers, local and international funders, TB patient advocates and former TB patients. In July 2021, the project team and the national TB programmes hosted two virtual workshops in Kenya and Malawi. The Kenya workshop was graced by the Head of the National Tuberculosis Leprosy and Lung Disease Programme (NTLP), Dr Waqo Ejersa. For Malawi, the workshop was graced by the Principal Secretary for Health, Dr Charles Mwansambo.

During the workshop, findings from the stakeholder engagements were presented by AFIDEP’s Sarah Karanja and Dr Tumaini Malenga. Thereafter, participants in each country were divided into three breakout groups and given a topic for discussion.

Findings from stakeholder engagements

In Kenya, there was a consensus that there is not enough data on the magnitude of patients that develop post-TB complications after completing TB treatment. Nonetheless, the NTLP in Kenya has shown support for a post-TB care programme by taking steps to include a chapter on post-TB lung disease in their Integrated TB, Leprosy and Lung Diseases Guidelines. Further to this, a Technical Working Group (TWG) for PTLD was formed; the NTLP established a sub-committee on research to identify research priorities on lung diseases and the post of PTLD coordinator was created.

In Malawi, a cohort study conducted by Dr Jamilah Meghji at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre provides some evidence that shows that 15-40% of former TB patients develop residual lung damage after TB treatment. However, no formal structures have been established to lead in the development and implementation of a post-TB care programme in the country.

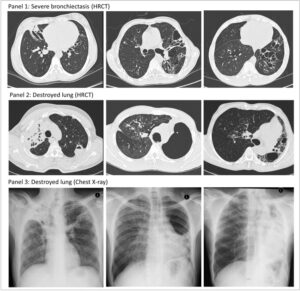

Image sourced from: https://thorax.bmj.com/content/75/3/269

In both countries, there was agreement that the unavailability of adequate data on the magnitude of patients that develop post-TB complications is a major challenge to implementing a post-TB care programme. The uncertainty over where in the health system a post-TB care programme should be placed also contributes to the lack of a post-TB care programme. Besides that, due to minimal evidence on the kind of complications that former TB patients experience, there is uncertainty over the content of a post-TB care package. However, in both countries, participants expressed that the post-TB care programme should be integrated with other care services to encourage compliance to care and to reduce the catastrophic costs that seeking care poses on patients.

Funding was also mentioned as a major challenge to implementing a post-TB care programme. The Global Fund is the largest funder for TB programmes globally and thus may consider funding post-TB care programmes where evidence exists on the need for such a programme. Other possible funders suggested include the StopTB Partnership, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) among others.

Defining the research agenda

A knowledge gap currently exists concerning post-TB care in Kenya. Participants suggested that patients be followed up from when they begin treatment until a year after treatment. Some tests that were suggested to identify lung complications include chest x-rays, spirometry, lung function tests and the 6-minute walk test. These tests would assist in the identification of common complications and aid in identifying the best treatment combinations. There is also a need to establish what services different levels of the health system will provide.

In Malawi, participants suggested the generation of additional data through monitoring systems and routine data collection to follow up with people who develop post-TB illnesses. There is also a need for data that links post-TB complications to other illnesses such as HIV, malnutrition, non-respiratory disabilities, cardiac complications and information on the quality of life of patients after TB treatment. Due to socioeconomic challenges that are experienced by former TB patients, there is also a need for information on the cost of equipment and the need to improve the technical expertise of health workers.

Participants recognised that post-TB care goes beyond medical care as some former TB patients fail to go back to their previous jobs due to lung impairments and others require psychosocial support as a result of stigma experienced during TB illness. As such, there is also a need for research on the socioeconomic challenges that these people experience and identify ways to assist them.

The Package of Post-TB Care

Kenya’s integrated TB guidelines outline that TB patients are to undergo a preliminary assessment including a chest x-ray to be done at baseline, 6 months and at the end of treatment. Spirometry will be conducted on patients whose chest x-rays present as normal but are experiencing symptoms. Due to the complex nature of post-TB complications, the package of post-TB care ought to be multifaceted to include social support, sensitisation on possible complications that may arise and the care to be provided by health workers. Patients also ought to know which level of the health system they can seek care from.

In Malawi, participants suggested the development of a symptom inquiry tool to identify any symptoms early. Due to the psychotherapy and psychosocial needs of patients, the Ministry of Health is working on deploying assistant physiotherapists and psychological counsellors to different health facilities. Participants also proposed task shifting in the delivery of post-TB care and learning from the implementation of the TB programme.

Models of Post-TB Care

In Kenya, participants suggested decentralised care to promote the engagement of a wide range of stakeholders and facilitate integration into the TB programme. Decentralised care would promote buy-in from the wider network on who receives care and what sort of care is provided. There was recognition that expertise for specialised care is concentrated at higher-level health facilities. Participants suggested borrowing from the MDR-TB patient follow up system that follows up patients for 2 years after treatment. Participants emphasised the importance of community engagement and advocacy for ownership and funding, longevity and inclusiveness in the process of implementation. To evaluate whether such a model would work in the country, they suggested that it be piloted in at least 2 counties before it is scaled up nationally.

Participants in Malawi believed that there is a need to decide whether the interventions are meant to be clinical, to address socioeconomic challenges or to reduce mortality from recurrent TB disease. Due to the decentralised nature of health care delivery in Malawi, participants community-based care by involving health surveillance assistants and social workers. However, having social workers and health surveillance assistants provide care at the community level would mean using human resources from the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare and therefore there is a need to link the two ministries in the delivery of care.

Planning for the future

Moving forward, there is a need to decide how interventions will be costed from both a health system and patient perspective, whether the package of care within a centralised or decentralised health system and which part of the health system will take ownership of the programme. Due to possible linkages that exist between the covid-19 and TB, post-TB care programmes should also consider people that have suffered significant injury from covid-19.

In Kenya, there is a need for the sub-committee on research for lung diseases to be revived to assist in the generation of evidence for post-TB lung disease and care. On the other hand, in Malawi, there is a need for the establishment of a technical working group with leadership and advocacy from the Malawi National TB Programme (NTP). Establishing a technical working group through the NTP would give it a good footing to take on securing resources for research and implementation.

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

Related Posts