Blogs

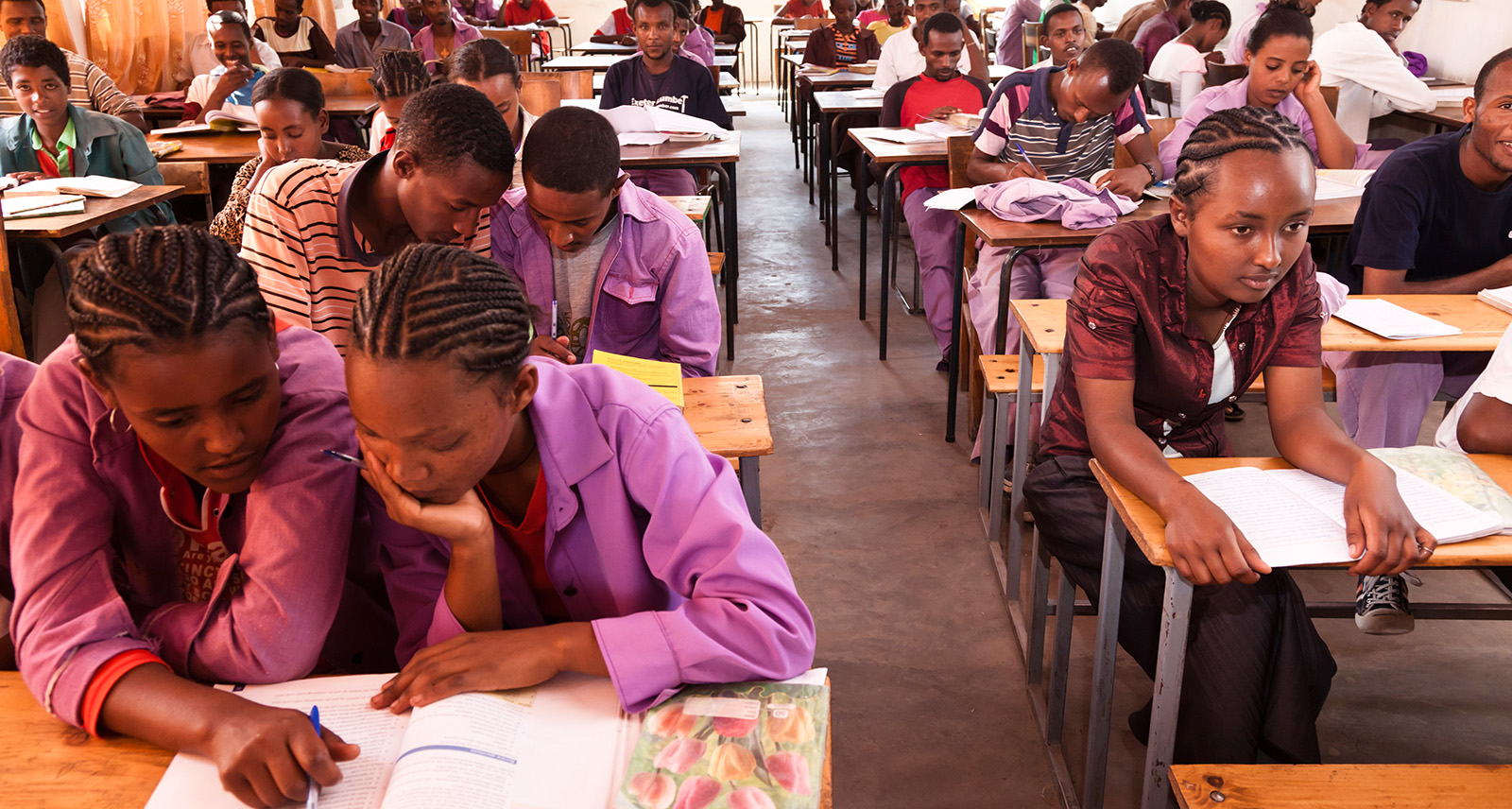

In Sub-Saharan Africa, women represent slightly more than half the working-age population. Yet women are far from being equal partners with men in the economy and society, facing an array of barriers to achieving their full economic potential, from restrictive cultural practices to discriminatory laws and highly segmented labor markets. Empowering women, defined as “the expansion of women’s ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability was previously denied to them,” will raise the productive potential of this half of the population, delivering a huge boost to the sub-continent’s development potential. A recent McKinsey study showed that Sub-Saharan Africa could add an additional 12 percent to its annual GDP (an estimated $300 billion) in 2025 if the gender gap is closed between men and women. Much of this gain would come from advancing gender equality in the world of work, which is closely tied to tackling gender gaps in society more broadly, by improving access to services in six areas: education, family planning, maternal health, financial inclusion, digital inclusion, and assistance with unpaid care.

What do the indicators on women empowerment show?

The African Development Bank’s Africa Gender Equality Index has a gender equality score that ranges from a low of 15 in Somalia to a high of 75 in South Africa. The score, based on three dimensions, economic opportunities, human development, and law and institutions, shows that African countries have a long way to go in achieving gender parity. Women in Sub-Saharan Africa have the lowest levels of equality globally in terms of access to essential services and enablers of economic opportunity. In general, women have lower educational achievement, lower employment opportunities, or less pay for the same work as men in both professional and technical jobs. They also have limited access to financial services including credit; in Chad, Niger, and Morocco, women have 50 percent less access than men. The unemployment rate of young women in Sub-Saharan Africa (25.3 percent) exceeds that of young men (20.2 percent). In addition, women are poorly represented in leadership positions. Access to health care services is also poor, leading to high maternal mortality ratios, unmet need for contraceptives, and a high number of unplanned births that have contributed to high fertility in the sub-continent.

Empowering Women to Build Economies

Women’s empowerment and fertility decline

African cultures have long valued large families as a matter of status, for the importance of family workers in agricultural economies, and to counteract high death rates for young children. Women are often bound by traditional cultural roles and norms that may dictate a lack of societal value and rights for women, including giving them less control over reproductive decisions. This preference for large families, in addition to the low status of women, underlies the high fertility observed in Sub-Saharan Africa. Lowering fertility rates is key to harnessing the demographic dividend, as fertility reduction will lower the child dependency burden and free resources for economic investment. But lower fertility rates will remain a pipe dream unless women’s empowerment is taken seriously. Improving women’s educational achievement, abolishing child marriage, improving child survival, and promoting labor force participation will reduce desired family size and thus fertility rates, improving economic growth and economic opportunities for women in particular.

Women’s empowerment and labor market participation

Educating women beyond primary school and ensuring they have access to quality jobs will increase their productivity and unlock their economic potential. Well-educated women who are engaged in the labor force will also increase the number of effective producers. Research suggests that women spend an average of 90 percent of their salary on their children and the health, education, and well-being of their family, while men spend only 30 to 40 percent on those same things. Spending on health, education, and the like creates ripple effects throughout the economy and promotes economic development. Thus women’s empowerment will improve economic well-being, reduce poverty, and improve the general economic outlook on the continent.

What are the policy options?

While most governments in Africa acknowledge that empowering women and girls is key to economic development, little has been achieved beyond the political rhetoric. For Sub-Saharan African countries to harness the demographic dividend, the economic growth that can be unleashed when a society transitions from an age structure dominated by dependents to one with a greater proportion of working-age adults, leaving women behind will no longer be an option. Governments and international policymakers and donors should focus on integrating opportunities for women educationally, economically, socially, and politically, by educating girls and women and giving them equal social and legal opportunities to those of men. Most of the potential increase in the output the continent will experience by abolishing the gender gap will come from women shifting to work in higher productivity sectors at par with the employment pattern of men, a shift that governments need to support. In addition, governments should bring primary health care to all with a particular emphasis on improving infant and child health, improving maternal health, and making available the full range of family planning services everywhere.

Empowering women through widening opportunities for education and work and improving access to credit will not only improve development but also will contribute greatly to fertility decline. Abolishing child marriage and educating women delays the age at entry into marriage and start of childbearing, and also increases their autonomy in making and implementing decisions related to reproduction. It also enables them to become champions of human development for their families and communities. The resulting improvement to their children’s welfare and life opportunities has multiplier effects that expand with each new generation, resulting in improved economic development of individual countries and the continent as a whole.

Eunice Mueni was a Southern Voices Network scholar at the Wilson Center from April to June 2016. She is a knowledge translation officer at the African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP), a member of the Southern Voices Network.

Related Posts